This thrilling account is the true story of how a former slave ship, the Black Joke, served with the British Royal Navy’s West Africa Squadron (WAS) to intercept slavers sailing from West Africa to the new world.

AE Rooks is a storyteller of some distinction. A polymath, she has completed degrees in theatre, law, and library and information science, and is currently reading for degrees in education and human sexuality. Her intellectual passions are united by what the past can teach us about the present, how history shapes our future, and above all, the importance of compelling stories.

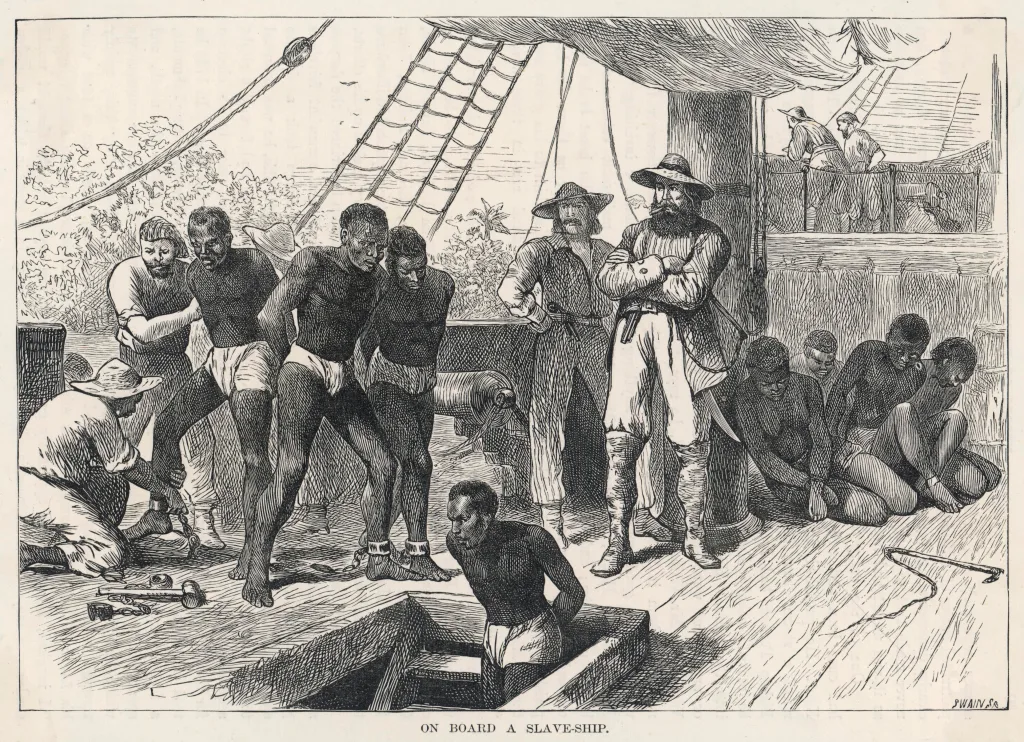

It is worth putting the Black Joke story into context. British involvement in the transatlantic slave trade began in 1562, and by the 1730s Britain was the world’s biggest slave-trading nation. An influential abolitionist movement grew in Britain during the 18th and 19th centuries, until the Slave Trade Act 1807 abolished the slave trade (but not slavery itself) in the British Empire. It was not until the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 that the institution of slavery was prohibited in directly administered overseas British territories.

‘Built for an emperor’

From 1808, the WAS made attempts to intercept illegal slave ships, but with few vessels available for patrols during the Napoleonic Wars success was extremely modest. From 1815 the navy could draw on more resources, but its vessels were often too old and slow to catch the slavers.

However, the Black Joke was different. Built in America and originally named the Henriqueta, Rooks describes it as “a ship so fine it may well have been built for an emperor”. It had a well-founded reputation for both its beautiful design and its ocean-going speed.

The ship was bought by a major Brazilian slave trader, Jose de Cerqueria Lima, who owned an extensive fleet of slavers. But in September 1827, sailing from Lagos with 569 enslaved Africans crammed into a 90ft by 26ft hold, its captain misjudged its ability to outrun the British ship Sybille. Forced to surrender, it was taken to Freetown in Sierra Leone, then a British colony and main base of the WAS.

Suppressing a vile trade

Upon reaching Freetown, Henriqueta was rapidly condemned as a slaver and sold at auction for £300.Acquired by the navy, she was renamed Black Joke after a popular ribald sea shanty, and so began the ship’s remarkable career as a scourge of slaving.

A dozen slavers were captured by the Black Joke. The Gertrudis was taken in January 1828 after a 24-hour chase and secured the release of 155 enslaved people, 80 of which were children. This came barely a week after the ship’s rechristening in Freetown, a remarkable feat considering that many of the ships in the WAS spent weeks or months patrolling the West African coast without encountering, let alone capturing, a single slaver.

After each chapter that outlines the ship’s accomplishments, the author reproduces the register that lists the enslaved people that had been found aboard. In a small way, this reveals its impact on individual human lives.

Rook also outlines the international treaties that complicated its work. If a suspected slaver could make a credible claim to belong to a nation, or deceive the authorities about the nature of its cargo, it could try to claim exemption from the WAS’s jurisdiction.

Rooks tells us that, for example, that of over 200 slaving ships leaving the coast of Africa each year in the late 1820s, just over 10% were sailing under the French or US flags. But, “since neither government had succumbed to British pressure to recognise (nominally) mutual right of search”, it was impossible for the Black Joke to search them.

And of course, as Rooks observes “this presumes the flag being raised was accurate. It should not be surprising that those who valued profit above life and human dignity were not above lying their faces off – and in every conceivable fashion and manner, with every means available – if it would prevent the WAS from capturing and condemning the illicit wealth imprisoned in their ship.”

And there was a further fact to take into consideration. If a WAS vessel was to take into custody a slaver that was not subsequently condemned by the naval court in Freetown, the WAS captain would be personally liable for the costs and damages for his mistake – a sobering consideration.

The fate of rescued Africans

Between 1807 and 1860, the WAS seized more than 1500 slave ships and “emancipated” 150,000 Africans.

But “emancipated” may not be the most accurate of terms. Enslaved Africans, on arrival at Freetown became British, whether they wanted to or not, and were given a number of options.

They could choose to become so-called apprentices (which Rook describes as ”slavery adjacent”) and shipped to the Americas, usually to harvest sugarcane for a period of no more than 14 years; join a segregated regiment of troops; or settle in one of the estates bordering Freetown to work under a supervisor with an allotment of land, a cook pot, a shovel, a spoon – and a yard and a quarter of fabric for some clothes. As Rooks notes with a withering observation, “nothing, sometimes not even slavery, seemed to offend British sensibilities like nudity”.

Those Africans who persisted in demanding true liberation were shipped off to the interior to fend for themselves. Rooks writes: “Recognising that emancipation without freedom was nothing much to speak of, some Africans pretended to docilely accept their new name or their new job, then melted away, either to escape the rigidity of liberty in Freetown, avoid being shipped out again, or simply to finally return to their homeland.”

In recent years, the brutal history of transatlantic slavery has returned to the public’s consciousness amid calls that African nations should receive reparations for its enormous enduring damage.

This compelling book is a useful addition to the canon, showing both the violence and inhumanity of the trade and the heartening role of those who stood against it.

Recent Comments