Shepparton, Australia – Brad Boon points to the towering mural, one of many that adorn the small rural town of Shepparton in the southeastern Australian state of Victoria.

The faces of indigenous heroes William Cooper And Sir Douglas Nicholls stare defiantly over the scattered shops in the harsh light of the Australian midday sun. Despite the onslaught of British colonization and discrimination, Sir Douglas became the first Aboriginal man to be knighted and appointed Governor of South Australia. He was also a talented Australian Rules football player.

Cooper, meanwhile, has long been an advocate for Aboriginal rights and is also known for protesting against the Nazi regime, seeing connections between the treatment of Indigenous peoples in Australia and the treatment of the Jewish people under Nazi Germany.

Both Cooper and Nicholls came from the indigenous Yorta-Yorta Nation – the traditional area around Shepparton. That their faces – along with other indigenous heroes – are emblazoned on the walls surrounding the city is a testament not only to the survival and resistance of the Yorta-Yorta peoples to brutal colonization, but also to their enduring legacy.

However, despite their long history of resistance and activism, the Yorta Yorta people are still fighting for their rights in 2023.

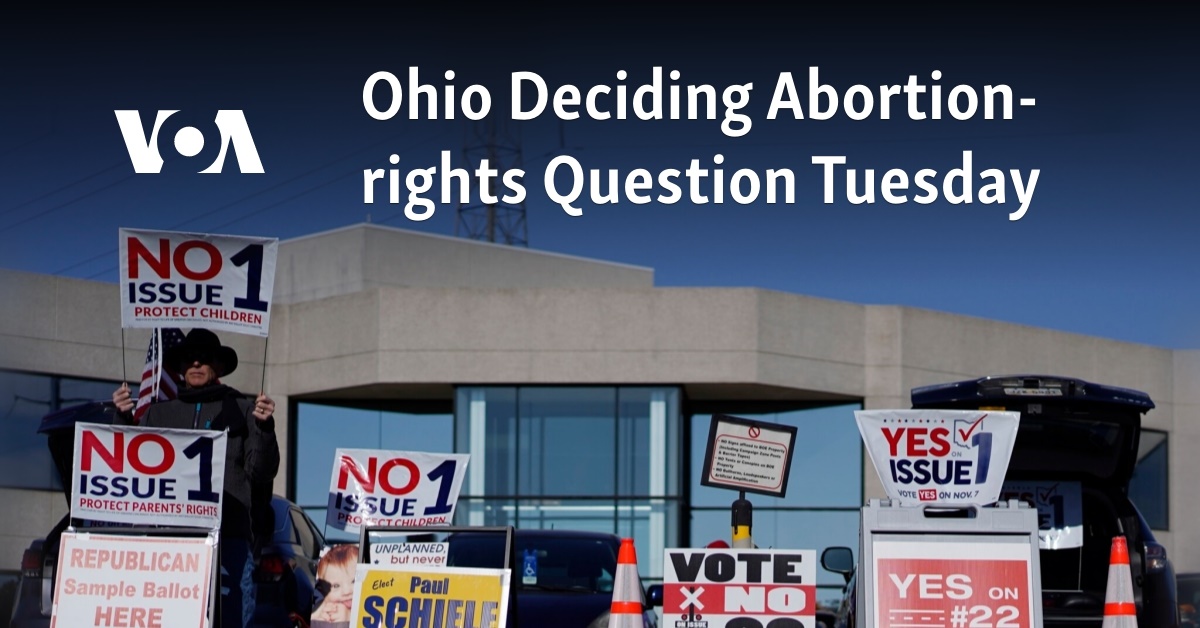

In October, Australia held a referendum to decide whether to introduce a constitutionally enshrined Indigenous “government law”.Vote to Parliament“.

The proposal was to establish an advisory board within the federal government to advise on Indigenous peoples’ issues and address the persistent inequalities they face in Australia.

Despite strong advocacy from his supporters, the proposal was rejected.

In Shepparton the no vote was heard even louder. More than 76.2 percent of the population voted against the vote – far higher than the national average of 60.62 percent. It was a disappointment for many of the Yorta Yorta, who make up one of the largest indigenous populations in the state.

Boon has lived in Shepparton for 17 years and is originally from the Kurnai Nation in southeast Victoria. However, he has a Yorta Yorta partner, has worked in the city’s Indigenous legal department and is a former player and now volunteer with the local Indigenous-run Rumbalara Football and Netball Club.

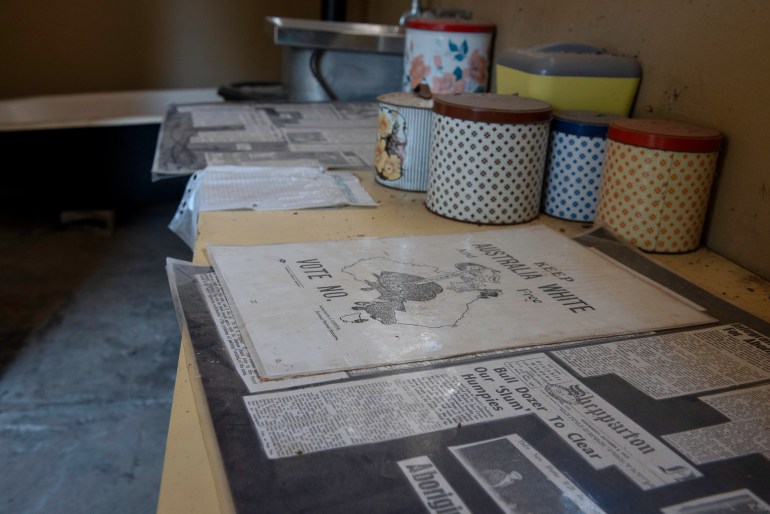

The referendum was characterized not only by the clear defeat, but also by the Racism and negativity that was typical of the debate.

Well-known local Indigenous rapper Briggs – Brad Boon’s brother-in-law – has been a strong supporter of Voice to Parliament and even held a free concert in Shepparton to drum up more voter support.

Despite the loss, Boon says there are many positive outcomes in small towns like Shepparton that are driven by Indigenous people and are rarely touted in the media or acknowledged in politics.

“Right now we’re just seeing bad things – domestic violence, sexual abuse, all the things they want to get people up in arms about,” he said.

“But they don’t talk about the good that’s happening in the state. And that’s what I think we need to do more of.”

Crowded into slums

Shepparton is a small town nestled on a floodplain just two hours north of Melbourne.

Surrounded by fragrant gum trees, rolling native bush and once-thriving river systems, the region has been home to the Yorta Yorta people for tens of thousands of years and maintains a rich cultural history that is still present in the local community.

Early colonials established sheep farming in the region and initially forced the Yorta Yorta into a settlement called Yorta Good luck in the 1880s and then in 1939 in slum housing on the banks of the Goulburn River.

The Yorta Yorta lived in huts made of tin and jute sacks in a flood-prone area known as the Mooroopna Flats. Leaders – including Cooper and Nicholls – pushed for better conditions at a time when Indigenous peoples across the country were denied equal wages and subjected to punitive laws that prevented their children from being placed in white institutions, known as “the , allowed Stolen Generations.

In Victoria, the effects of colonization were even more severe than in the rest of the country. It is estimated that at least 50 massacres occurred, some killing up to 200 indigenous people, often referred to as genocide by indigenous scholars.

It’s a story that underpins both the struggle and success the community has made since the days of Cooper and Nicholls, but racism is still deeply rooted in the small town.

Heidi Knowles says she experiences racism on a regular basis, particularly when she wears a T-shirt with the Aboriginal flag.

She says shop owners assume she will steal something, perpetuating the stereotype of Indigenous people as criminals.

“Maybe I’ll be followed in the supermarket and feel uncomfortable. Don’t get me wrong,” she said. “But I have nothing to hide.” Knowles is proud to be an Indigenous woman.

“I’m wearing my Koori [Indigenous] Up with pride and you will see me [in it] every single day,” she told Al Jazeera.

The 39-year-old mother works as an operations and student success manager at the local Academy of Sport, Health and Education (ASHE), a high-performance center for predominantly Indigenous young people.

She says such a center is crucial for Indigenous students who may experience racism and discrimination at their local school or simply don’t fit into the mainstream education system.

“Our little ones fell through the cracks in regular school. So they come here because it is a culturally safe and culturally appropriate place where they can reach their full potential,” she said.

Knowles herself was once a student at ASHE and told Al Jazeera that growing up in Shepparton she faced many barriers to finding work, which she believes was due to discrimination.

As a result, she knows firsthand how important Indigenous education programs are.

ASHE students have gone on to earn doctorates and become nurses and sports professionals.

“In a culturally safe place you feel connected to your culture. And when you feel connected to your culture, that plays a big role in achieving what you want to achieve,” Knowles said.

“Because when you have a connection to the culture, the sky is the limit.”

Rooted in culture

Near the ASHE Education Centre, the Shepparton Art Museum is home to another local Indigenous success story: an Indigenous art space called Kaiela Arts was recently established.

Kaiela Arts is modeled after the arts centers typically found in central or northern Australia. It sits on the river and is surrounded by the ubiquitous Australian rubber tree.

Tammy Atkinson, one of their artists, says the works created by the Yorta-Yorta community are very different from the more familiar dot paintings from the desert region that are typical of Aboriginal art.

“What they consider to be Aboriginal art is different to Aboriginal art down here,” she said. “Down here, this art is more about narrative storytelling and lines.”

Like many of the successful programs developed in Shepparton, Kaiela Arts began as a community initiative with Yorta Yorta elder Les Saunders, who collected art from people’s homes and sold the works privately.

Today, Kaiela Arts is one of 90 recognized Indigenous arts centers across Australia, hosting programs for women, children and youth.

Artists and community members Belinda Briggs and Lyn Thorpe share the same enthusiasm for Kaiela Arts and tell Al Jazeera that the youth arts programs will help ensure a strong culture for the Yorta-Yorta community well into the future.

“[Young people are] “Like the young rubber tree,” said Briggs. “We want them to one day be old eucalyptus trees with strong roots and know where to find the water that feeds them and nourishes them. And then they pass it on to the next generation.”

As well as being an artist, Lyn Thorpe led the development of a photo wall at the local Rumbalara Football and Netball Club depicting generations of family history.

She said even something as small as compiling family photos was a form of resistance to colonization, which – through the Stolen Generations – aimed to divide and erase Indigenous families.

“We are talking about generations of people constantly trying to rebuild. If it’s taken down, we’ll rebuild it,” she said.

A different kind of reconstruction is underway on the outskirts of the city.

The Munarra Center for Regional Excellence will serve as a purpose-built, modern facility for the Yorta Yorta to combine education, culture, arts and sport.

Another local initiative, the Munarra Center, is scheduled to open in 2024 and will serve as a hub for the local Yorta-Yorta population, with the aim of developing the next generation of leaders.

The referendum result may have been a disappointment, but in Shepparton the Indigenous community is forging its own path in the fight for equality.

“For us, we just have to keep our heads down and our butts up and just hang in there and chug along and get the results that we want for our community,” Boon said.

“It’s not newsworthy, but it should be. Because little things like this really give our mob strength [people]. Our little kids see that and then they like to walk around and talk about being Aboriginal and what it means to them and see the good that happens.”

Recent Comments