A good score on China’s annual national civil service examination is a requirement for any Chinese candidate who wants to be considered for the tens of thousands of public service vacancies that the government tries to fill each year.

Many of the vacancies are reserved for young Chinese graduates.

When 22-year-old graduate Du

Some applicants even hire tutors to prepare them for the exam.

Candidates are extensively tested on their general knowledge and analytical skills, whilst in recent years their understanding of “Xi thought” – Chinese President Xi Jinping’s ideology and vision for China.

Despite her months of preparation, Du knew the chances that her test score would get her closer to a government job were slim.

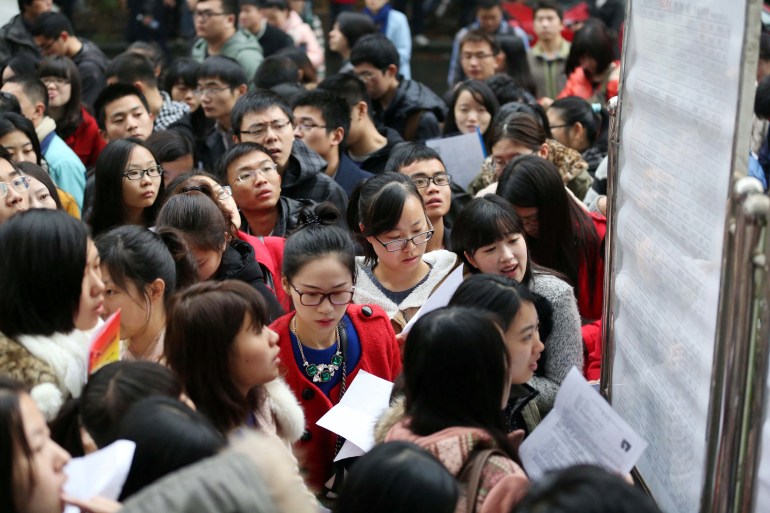

As she began testing, so did millions of other Chinese youth in hundreds of Chinese cities.

“The competition is tough,” Du told Al Jazeera.

This year the chance of getting a job in the public sector was 70 to one.

Therefore, Du was surprised and thrilled when she learned that she had passed the exam well and subsequently got a job as an organizer at the local Chinese Communist Party (CCP) office in Shijiazhuang.

This year the competition appeared to be even tougher as the number of candidates who registered for the exam at the end of November exceeded the three million mark for the first time.

The number of vacant government positions hasn’t kept up, so the odds of getting a job like yours have dropped from 70 to 1 to 77 to 1. according to the state-run Global Times.

You’re not surprised at the high number of applicants.

“I think a lot of young people in China really want stable jobs now,” she said.

Job security is an “iron rice bowl”

It was the appeal of stable employment that persuaded you to take the civil service exam last year Economic turmoil in China.

“After completing my studies I felt a bit lost, I didn’t know what I wanted to do,” she told Al Jazeera. “But I knew I wanted a job where I could feel safe and have free time, and that sparked my interest in government work.”

Although employment in the Chinese public sector is rarely as well paid as comparable employment in China’s private sector, there are other benefits. Civil servants typically have access to better health insurance, preferential retirement planning, regular bonus payouts and secure lifelong employment.

The security that comes with public office has earned him the nickname “Iron Rice Bowl.”

Iron rice bowls are coveted by some traditional Chinese parents for their children – not only for stability reasons, but also because some view obtaining such jobs as recognition of excellence by the state.

For you, an important aspect of life as a civil servant is working hours.

“I work 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and don’t have to work on weekends,” Du said.

Many of Du’s friends in the private sector work there 996 system – 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., 6 days a week.

“Compared to them, I have a lot more free time to pursue my hobbies,” she said.

Yang Jiang was also not surprised by the record number of applicants for China’s civil service exam this year.

Jiang is an expert on China’s economic policies and a senior researcher at the Danish Institute for International Studies.

The number of applicants has risen rapidly in recent years; according to Jiang, one reason for this is the equally high number of Chinese graduates entering the job market.

In 2023 alone, almost 11.6 million Chinese will have completed their studies, more than ever before.

But the overarching reason for the high number of applicants for the civil service exam is the Chinese economy, Jiang told Al Jazeera.

“The economic situation in China is uncertain,” she said.

The Chinese economy is struggling to reach the growth rates of previous years, the real estate market is in the deepest crisis in decades and foreign direct investment recorded a deficit for the first time in July-September 2023.

Things look particularly bleak for Chinese graduates: youth unemployment hit a record 21.3 percent in June, before authorities stopped publishing the figures.

“Particularly in the private sector, there were a lot of layoffs during the economic downturn,” Jiang said.

“This has naturally led to more Chinese graduates looking to the public sector for the kind of job security that is currently lacking in the private sector,” she said.

“You can’t make us disappear.”

Like you, 23-year-old Chris Liao from southern China’s Guangdong Province completed his master’s degree in public administration last year. He also registered for the civil service exam.

“I failed the written test,” he told Al Jazeera.

Afterwards, Liao was unable to find a job in his field of study and was forced to work as a chef for a while before moving back to live with his parents in the area around Guangzhou, Guangdong’s largest metropolis.

He is now one of the millions of unemployed young people in China.

“I feel like life got really difficult when COVID hit, and it hasn’t stopped getting difficult since,” he explained.

Liao believes the government’s COVID-19 strategy is the cause of many of the economic problems plaguing China today.

“Therefore, it is the government’s responsibility to do more to improve the situation,” he said.

According to observers, the large number of unemployed youth in China’s major cities is a major concern for the party-state.

A communist organization in Liao’s Guangzhou even put forward a plan in March to send unemployed youth to the countryside to promote rural development.

Such a plan dates back to Chairman Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 1970s, when millions of urban youth were sent to the countryside during a period of political and social upheaval that resulted in human deaths at least two million people.

In January, President Xi also spoke of Chinese youth “revitalizing” the country.

However, Liao does not believe that such plans are realistic in this day and age.

“You can’t let us disappear into the countryside,” he said.

“There are too many of us and there are more and more of us.”

Recent Comments