Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia – In the elegant offices of a law firm among the skyscrapers of the Malaysian capital, 85-year-old Lim Kok’s thoughts return to a crime committed by British forces Three quarters of a century before.

The intervening decades have not faded Lim’s memories of when Malaya was a colony in the declining days of the British Empire.

To slow the sunset on its colony in Southeast Asia, London sent thousands of British and Commonwealth troops to suppress a local movement fighting for independence after World War II.

Lim was only nine years old when his father, a hard-working Chinese overseer on a rubber plantation, was shot dead along with 23 other innocent workers in a hail of bullets in what is still known as the Batang Kali massacre.

Lim said he lost more than his father that day.

He lost a family.

After her husband and the family breadwinner died, Lim’s mother was left to raise six children alone – an impossible task for a poor rural household in the late 1940s.

Lim’s mother had to give up her youngest child, a newborn girl, for adoption. Lim was later sent to live with a great uncle in Kuala Lumpur.

Not only was Lim’s family torn apart, but the British troops who carried out the massacre attempted to cover up the atrocity by accusing their victims of being associated with the pro-independence communists.

The truth would emerge years later when journalists, researchers and court cases confirmed the innocence of those killed by British soldiers at Batang Kali.

However, they still exist today No compensation or official apology by British authorities who have resisted calls to open an investigation into the massacre that took place 75 years ago this week.

“I knew my father was a real rubber tapper,” Lim told Al Jazeera when asked about the colonial state’s attempt to portray the massacre victims as rebels.

The false accusations never made him “feel bad” when he was younger, he said.

“The only bad thing is that they were massacred by the British soldiers.”

Despite being in his mid-80s, Lim is sprightly and energetic and has not given up the fight to hold the British government to account for “the suffering that we and the other relatives of the murdered people have suffered.”

“As youngsters, we suffered a lot. Even my brothers and sisters… They have to start looking for work at a very early age just to make a living,” he said in an interview earlier this year. “They suffered a lot.”

The latest fight to hold British authorities to account began in 2008, when the father of Kuala Lumpur-based lawyer Quek Ngee Meng launched a campaign for justice after researching the incident in retirement.

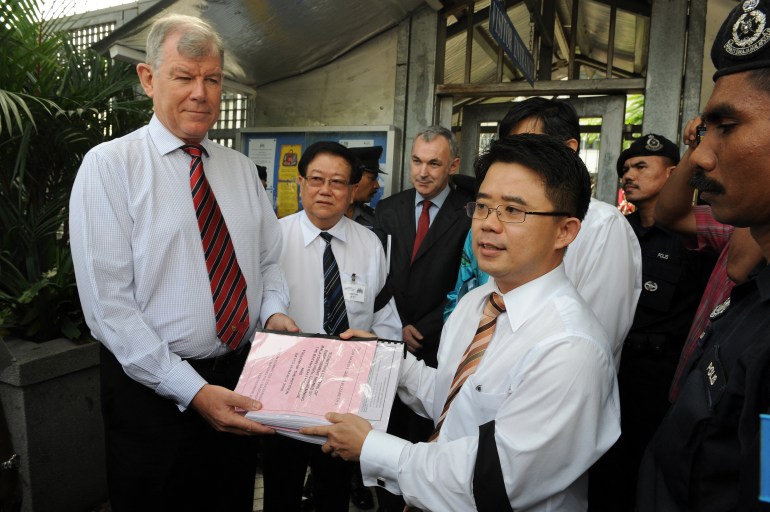

When his father died in 2010, Quek stood up for the victims of Batang Kali.

The campaign for an official inquiry has taken advocates from the London High Court to the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

Quek said the massacre had a generational impact on the families of the slain men, who faced economic hardship and poverty in addition to the trauma of their loved ones’ violent deaths.

Many of the victims’ families could not afford to provide their children with a good education. Some gave their children up for adoption. Others married young or agreed to arranged marriages just to keep their families afloat after losing their breadwinner.

“The families were actually broken,” Quek told Al Jazeera, explaining that it took generations for the victims’ families to improve their economic and social circumstances.

“Actually, it wasn’t just the 24 or whoever was killed. Many, many people are victims of this,” he said.

Quek remembers that legal action was not her first choice. An apology and an agreement would have been enough for the relatives, but a letter to the British authorities requesting negotiations was ignored.

“There was no middle ground we could reach…” No offer for talks. We just have to continue on this legal path and yes, we lost on a technicality,” he said.

“I felt sorry for Lim Kok and everyone else I couldn’t get compensation for,” said Quek, who has worked on the campaign as a volunteer for years.

“But what I can say is this: all the judges agree that the British soldiers committed an atrocity at the time. And the fact, the real fact, is that these villagers are not guilty of any crime.”

“They were not communists. There is no evidence that they were sympathizers,” he said.

The details of the Batang Kali massacre are horrifying.

According to court documents, in the early evening of December 11, 1948, a Scottish Guard patrol with 14 soldiers entered the remote settlement in Batang Kali, located among densely forested hills about 60 km (around 40 miles) north of Kuala Lumpur. About 50 adults and a few children lived in the settlement, who worked on the surrounding rubber plantation, which belonged to a Scot.

The British soldiers separated the men from the women and children and locked them overnight in a long wooden hut where they were interrogated. The soldiers carried out mock executions to frighten the unarmed male villagers in the hope of gaining information about rebels who might be nearby.

That night the first victim was shot.

The next morning, the women and children, as well as a traumatized man, were loaded onto a truck and driven away from the plantation. The hut where the 23 men had been held was opened and within the next few minutes everyone was shot.

With bodies strewn everywhere, the soldiers set fire to the workers’ huts and the patrol moved on, later returning to their base.

The first newspaper report in the days after the massacre described the slain men as “bandits” who had been shot as they tried to escape, and claimed a quantity of ammunition had been discovered.

Shortly afterwards, the British War Office officially declared the murders a “very successful operation”.

When the truth emerged about what had actually happened, a rudimentary investigation led by British legal officials in the colony was conducted and concluded within days.

Based on statements from soldiers rather than villagers, it was concluded that nothing had happened in Batang Kali that “warranted criminal proceedings.”

Recent Comments