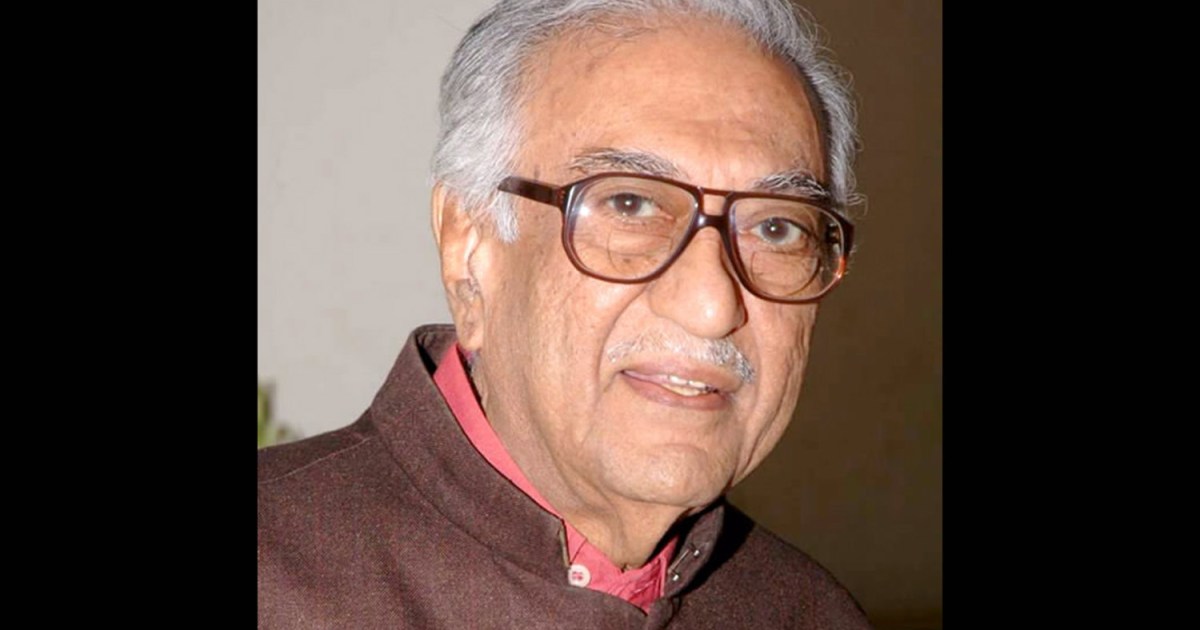

New Delhi, India – For three generations of Indians, Bollywood and radio meant one name: Ameen Sayani. On Tuesday, the voice that penetrated the homes of hundreds of millions of people was silenced for the last time.

Sayani, who began his career in the early 1950s with a weekly countdown show of Bollywood songs and dominated Indian broadcasting for more than six decades, died in Mumbai after suffering cardiac arrest. He was 91.

To his audience, he was much more than just a presenter – blessed with a warm, friendly voice, he cultivated a cheerful, inimitable broadcasting style that evoked the image of a sincere friend who spoke directly to every listener over his radio. A friend who built a cult following, who knew no generational difference and who nurtured a love affair between Bollywood songs and his listeners.

His original radio show, Binaca Geetmala, ran for 42 years, popularizing several lyricists, composers and singers and even saving many films from oblivion.

“Radio was king then and he was the king of kings,” Anurag Chaturvedi, a journalist and author who knew Sayani well, told Al Jazeera.

Over the course of a career that spanned much of independent India, Sayani recorded at least 50,000 radio programs, lent his voice to 19,000 jingles, hosted TV shows and did voice acting and guest appearances in a number of Bollywood films, often as a radio presenter.

“If you look at our radio history from 1927, the year radio was founded in India, till date there is only one voice, one name that is remembered – Ameen Sayani. He was a superstar, his voice was like a gift from heaven,” Pavan Jha, a musicologist, told Al Jazeera.

All India Radio (AIR), India’s national radio station, is also called Akashvani, which means heavenly announcement or voice from heaven in Hindi.

Hindi-Urdu, women first and a touch of defiance

Ameen Sayani’s radio career began with a ban.

In the winter of 1952, Balakrishna Vishwanath Keskar, India’s Federal Minister for Information and Broadcasting, banned film songs from national broadcasters, calling their lyrics irrational, vulgar, Westernized and a threat to Indian classical music.

On AIR, Hindustani and Carnatic classical music replaced film songs as announcements and news broadcasts became increasingly Sanskritized.

Radio Ceylon, a radio station founded in Colombo, Sri Lanka during World War II to provide music and news to British soldiers stationed in South Asia, saw an opportunity.

It hired a sponsor – Binaca Top, a toothpaste brand – and a studio owner and producer, Sayani’s older brother Hamid, based in what was then Bombay, now called Mumbai.

On December 3, 1952, a few months after Keshar’s ban, the powerful military broadcasters of Radio Ceylon broadcast Binaca Geetmala (garlands of songs) to homes across India for the first time, with 20-year-old Ameen Sayani’s cheerful, cheeky greeting: “ Behno aur bhaiyon, aap ki khidmat me Ameen Sayani ka adaab (Sisters and brothers, Ameen Sayani is at your service with respectful regards)”.

The show’s theme tune was from a silly but catchy Hindi film song – Pom-pom, Dhin-dhin Goes the Drum – and Sayani’s greeting was in Hindustani. Hindustani, a mixture of Hindi and Urdu, was the language of Bollywood films and songs and the language of the people.

Sayani’s fresh, cheerful style, his buoyant, defiant tone and his decision to reverse the order of the traditional “brothers and sisters” greetings made the show an instant success.

“There was gender sensitivity and Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb in this greeting,” Chaturvedi said, referring to India’s traditionally syncretic Hindu-Muslim culture.

He was a cultural ambassador and publicist of Hindi-Bollywood music

Sayani was born in 1932 in an elite family in Mumbai. His mother, Kulsum Patel, was Hindu and his father, Dr. Jaan Mohamad Sayani, Muslim. Both were involved in the Indian freedom movement.

Sayani attributed his fluency and ease in Hindustani to years of helping his mother edit and print Rahber (meaning “guide” in Urdu), a biweekly diary. In an interview, he once recalled a note that Mahatma Gandhi had written to his mother: “I like the mission of ‘Rahber’ to unite Hindi and Urdu. May it succeed.”

Sayani and his brother recorded the Binaca Geetmala show in their Bombay studio and sent magnetic tapes by plane to Radio Ceylon, outside the jurisdiction of the Indian government.

The show’s format was simple: based on listeners’ desires and record sales, Sayani performed 16 Hindi film songs in ascending order of popularity. Sayani has been compared to legendary US presenter Casey Kasem, who dominated his country’s music radio with his American Top 40 show. But while Sayani expressed his admiration for Kasem in later interviews, his show preceded Kasem’s by nearly two decades, setting a pattern for the world to follow.

While the Indian government kept film songs off its airwaves, Sayani celebrated Bollywood songs and elevated them to a popular art form. He introduced each song with the name of the author, composer and singer and shared an anecdote about them, their struggles and their commitment.

According to Jha, in the late 1980s, when Amitabh BachchanWhen the congressman was indicted for his alleged involvement in a corrupt defense deal, the release of his film Shehenshah was repeatedly delayed. “Binaca Geetmala kept the film alive by playing the song Andheri Raaton Mein (On Dark Nights) over and over again for months,” he said.

Sayani was also a suave marketer. He periodically said, “Give me a Binaca Top smile,” promoted the sponsor’s toothpaste, and connected with his listeners.

“That sound in his voice, that instant connection [he had] with listeners… He was more than a radio host. He was a cultural ambassador, an advertiser and publicist of Hindi-Bollywood music,” said Jha, who, like thousands of others, sat in front of his radio set every Wednesday at 8 p.m. with a notebook to jot down information about songs and their ranking.

“Everyone in the house was listening to his show — women cooking in the kitchen, men in the living room, Bauji (grandfather) on the porch,” Jha said.

Letters from Jhumri Telaiya to this voice from the heart

Ameen Sayani, whose career is synonymous with the golden era of radio in India, also hosted other popular shows including the weekly Bournvita Quiz Contest, which he took over after the death of his elder brother.

He created hundreds of 15-minute radio commercials and sold toothpaste and headache pills on radio and television. But apart from Bollywood, it was the dusty, nondescript town called Jhumri Telaiya that he really made famous across India.

At Binaca Geetmala, Sayani asked listeners to email him their favorite songs and their rankings: he read some of the scores on air. This spawned eager radio clubs and passionate letter writers across the country, including in the mica mining town of Jhumri Telaiya in the northern Indian state of Jharkhand.

Rameshwar Prasad Barnwal, a mining tycoon, was reportedly the first resident of Jhumri Telaiya to start sending postcards with his farmaish (song wish). Sayani was perhaps intrigued and regularly read out his request and the name of the city in his sing-song style on his show.

While many listeners thought Sayani had invented this strange-sounding city as a joke, writing letters in Jhumri Telaiya became a madness and an ego trip. Residents sent several letters each week and reportedly even bribed postmen not to post other people’s letters so that they would have a better chance of being picked up by Sayani.

At its peak, Binaca Geetmala, which eventually moved from Radio Ceylon to the All India Radio network and ran until 1994, had about 400 radio clubs and thousands of individuals who wrote their concerns to Sayani daily.

“He knew the art of radio announcements. He used flowery language, playing with his voice and his words. But his style was decent… He had a lot of adab (subtlety),” Chaturvedi said.

“Ameen Sayani was special. His voice stood out because it came from the heart.”

Recent Comments